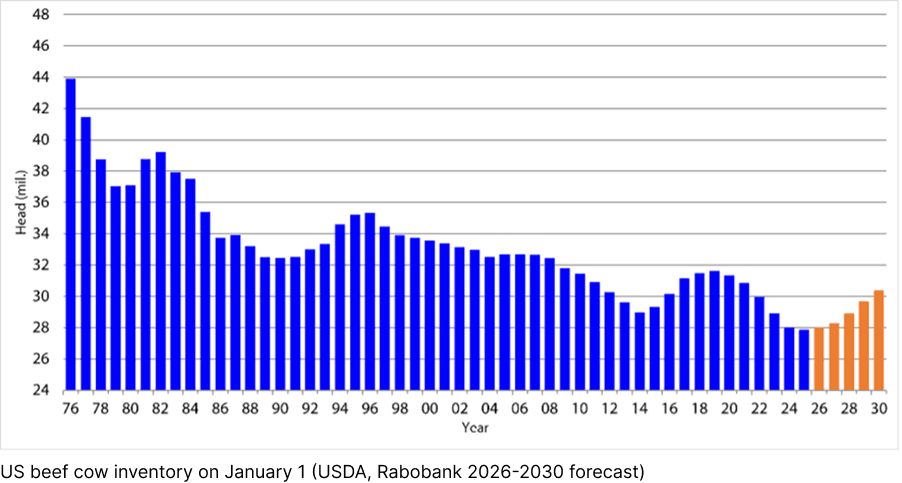

Rabobank expects the Jan. 1, 2026, beef cow inventory to be 28 million head — up 200,000 head from the prior year. A second increase of less than 500,000 head is likely over the following year.

Cow liquidation is in the rearview. Heifer retention is underway. The U.S. cattle cycle is officially shifting into rebuild mode, but this recovery will not be a stampede. It’s shaping up as a slow, strategic climb.

Beef processing bottlenecks, persistent drought, soaring feed costs, labor shortages and post-pandemic friction kept cow-calf margins relatively tight from 2016 to 2022. Some of those pressures have eased, but with herd numbers set to grow, others could easily resurface. As producers hold back more heifer calves this fall, herd replenishment remains a cautious and calculated exercise.

Rabobank expects the Jan. 1, 2026, beef cow inventory to be 28 million head, up 200,000 head from the prior year. A second increase of less than 500,000 head is likely over the following year. In short, do not expect dramatic shifts early in this rebuilding effort. From 2024 to 2026, the nation’s beef cow herd will hold relatively steady.

More meaningful herd growth is forecast from Jan. 1, 2027, into the early 2030s. But even then, the peak inventory projection is likely to be 500,000 to 1 million head below the 2019 highs, and that is not necessarily a bad thing.

Thanks to long-term efficiency gains across the U.S. beef sector, a rebuild topping 30.5 million cows might be more than enough to hit new record high in total production. Per capita beef supplies could reach levels not seen in more than two decades. Still, adding upward of 2.5 million cows during this next phase will be complicated.

According to the latest Farm Journal State of the Beef Industry survey, just 47% of producers are considering expanding their cow herd within the next five years, a four-point drop from last year’s already modest number.